Aristotle has dome some particularly helpful work on how to sort out what a thing is, or perhaps, why a thing is. Aristotle would teach us to ask four questions about a thing:

Here is the audio of the interview with me and Dr. Schulz, as well as the text from Aristotle:

- Out of what has this type of thing come? (The Material Cause)

- What type of thing is it? (The Formal Cause)

- By means of what is it the type of thing it is? (The Efficient Cause)

- For the sake of what is it the type of thing what it is? (Final Cause)

Here is the audio of the interview with me and Dr. Schulz, as well as the text from Aristotle:

Here are Dr. Schulz's suggestions for approaching this metaphor:

1. Aristotle’s Cross Examination of Nature

a) Read Aristotle’s Physics, Section 3 on causes. Aristotle’s text is a must-read! Read it twice, please. The Loeb edition has facing pages of Greek and English. Online you will find an English text with Greek options at http://www.ellopos.net/elpenor/greek-texts/ancient-greece/aristotle/physics.asp

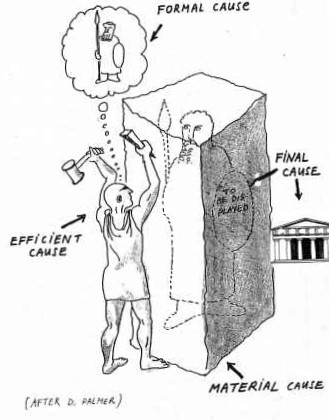

b) A diagram for the so-called Four Causes can be seen at the beginning of this post.

c) Now, Aristotle’s term, the Greek term translated “cause” is misleading to us in modernity. For an example of the wild concepts, illustrations and odd un-Aristotelian notions that stem from this misunderstanding, have a look at the Wikipedia article on the four causes (but not until we’ve looked at Aristotle’s Greek first! (Curmudgeonly philosophy professor’s observation: Fruitful and evocative Greek terms inevitably get reductive-ized when rendered in Latin, horribile di!)

d) Aristotle’s term is in fact aitia, which I render as “cross examination”. Here is support for my rendering from Liddell and Scott.

αἴτιος αἰτέω

I.to blame, blameworthy, culpable, Il., etc.: comp., αἰτιώτερος more culpable, Thuc.; Sup., τοὺς αἰτιωτάτους the most guilty, Hdt.; τινος for a thing, id=Hdt.

2.as Subst., αἴτιος, ὁ, the accused, culprit, Lat. reus, Aesch., etc.; οἱ αἴτιοι τοῦ πατρός they who have sinned against my father, id=Aesch.:—c. gen. rei, οἱ αἴτ. τοῦ φόνου those guilty of murder, id=Aesch.

II.being the cause, responsible for, c. gen. rei, Hdt., etc.; c. inf., Soph.: Sup., αἰτιώτατος ναυμαχῆσαι mainly instrumental in causing the seafight, Thuc.

2.αἴτιον, τό, a cause, Plat., etc.

Liddell and Scott. An Intermediate Greek-English Lexicon. Oxford. Clarendon Press. 1889.

accessed Jan 2015 at http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.04.0058%3Aentry%3Dai%29%2Ftios

Taking aitia as a cross-examining we see that Aristotle is in effect insisting on a more complete account of things than we usually settle for.

Why makes this thing the type of thing it is? (Aristotle’s Cross-Examination)

Q1. Out of what has this type of thing come?

Via Latin the answer obtained by identifying: The Material Cause:

The material cause points to "that from which, as a constituent, an object comes into being." (For instance, the bronze of a statue.)

Q2. What type of thing is it?

Via Latin the answer obtained by identifying: The Formal Cause:

The formal cause embodies the essential nature (all essential attributes) and represents the model or archetype of the outcome; conceptually it is expressed in the definition (logos). (It is the idea of the statue as present in artist's head.)

Q3. By means of what is it the type of thing it is?

Via Latin the answer obtained by identifying: The Efficient Cause:

The efficient cause is "the source of the change or rest"; it is the moving cause: "what makes of what is made and what changes of what is changed" (the sculptor who makes the statue).

Q4. For the sake of what is it the type of thing what it is?

Via Latin the answer obtained by identifying: The Final Cause:

The final cause states "that for the sake of which" a thing is the type of thing it is, or why a thing is done, or, in other words, it explicates something's end in terms of its species or class or type of thing that it is (the final shape or the effect on the audience which admires the statue).

Note: Although Aristotle himself holds all these four causes responsible for any real change and movement (aitia in Greek are those things that are "guilty" or responsible for something), they are rather demarcation points of change as revealed in our language […] In difference to the modern concept of causation, which always implies a sequence of two events, Aristotle envisions causation as a single event of double actualization … [that we can think of us a continuation of a thing according to its kind although he uses a scheme of recognizing a things potential to be what that kind of thing is, based on that kind of thing’s complete story, so to speak. GPS]

Heavily adapted from http://www.willamette.edu/~sbasu/poli212/AristotleonCause.htm

e) By the way, Aristotle’s term for final cause or the cross-examination question, “What is the thing for?” is telos. While Kittel says that the New testament usage of telos has nothing in common with Greek philosophy (see the Kittel quote below) – and although I often try to re-think this when teaching Aristotle and especially when preaching John 19:30 – I think that those of us who are called to preach the Word may do a better job of preaching that pluperfect word from our suffering Savior, “It is finished!” with Aristotle as a footnote to the word telos.

τέλος.

There are in the NT no statements about the telos of men which stand in formal analogy to Greek sayings (→ 50, 3 ff.). The NT puts the matter differently and sayings which are teleological in content do not set man in the centre, → II, 428, 12 ff.: II, 327, 16 ff.

[…]

Fn: R. 6:21 f. can hardly have been understood thus by the author (→ 55, 5 ff.) or the readers or hearers, esp. as the sayings are always negative apart from R. 6:22, and could only be taken as definitions of telos in an ironically paradoxical sense.

Kittel, G., Bromiley, G. W., & Friedrich, G. (Eds.). (1964–). Theological Dictionary of the New Testament (electronic ed., Vol. 8, p. 54). Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

f) For a more detailed consideration of the traditional four-question examination of things – four dimensions of the thing’s story, if you will – please consider S. Marc Cohen’s class outline The Four Causes at http://faculty.washington.edu/smcohen/320/4causes.htm

g) Compare and contrast what the apostle Paul says of Jesus in regard to the entire cosmos or universe (“all things visible and invisible) in Colossians 1:15-2:3. Does it sound like the apostle is both thinking in an Aristotelian manner about causes or aitiai while at the same time demonstrating a philosophy kata Christon or based on Christ Himself (see Col 2:2:8-15)?

h) A crucial area for our understanding of Aristotle’s four causes or aitiai is in regard to his definition of the human being (that is, our kind of being) in his Politics, Book 1 as zoon logon echon. Aristotle’s four-question thinking about what kind of thing a particular member a species follows from this Four Causes cross-examination. This is foundational for natural law theory in ethics and is something that Martin Luther takes for granted (and then surpasses) with his theological understanding of the human being’s formal and final causes in his 1536 Disputation Concerning Man. These theses may be found here.

Gregory P. Schulz, all intellectual rights reserved, January 2016

There have been many times in my reading of theology that I've thought, "I need to understand Aristotle's Four Causes!" So many Christian theologians assume these four causes that a basic understanding of them is particularly helpful, and the conversation with Dr. Schulz gave me that basic understanding.

Aristotle's Cross Examination of Nature, as Dr. Schulz reminds us, is a better way to get at what a thing is. Our modern addiction to Scientism tempts us only to ask about the Material Cause. Aristotle reminds us, "There's more to know about a thing!" And Dr. Schulz also helpfully reminds us that this is profoundly helpful when we consider ethics, especially bio-ethics and questions about our humanity, like abortion.

But Aristotle, like Plato, falls short, especially when he applies his cross-examination to humanity. There is more to say about humanity than reason can say. Luther says this in his disputation on man:

Aristotle's Cross Examination of Nature, as Dr. Schulz reminds us, is a better way to get at what a thing is. Our modern addiction to Scientism tempts us only to ask about the Material Cause. Aristotle reminds us, "There's more to know about a thing!" And Dr. Schulz also helpfully reminds us that this is profoundly helpful when we consider ethics, especially bio-ethics and questions about our humanity, like abortion.

But Aristotle, like Plato, falls short, especially when he applies his cross-examination to humanity. There is more to say about humanity than reason can say. Luther says this in his disputation on man:

- 13. For philosophy does not know the efficient cause for certain, nor likewise the final cause,

- 14. Because it posits no other final cause than the peace of this life, and does not know that the efficient cause is God the creator.

- 15. Indeed, concerning the formal cause, which they call soul, there is not and never will be agreement among the philosophers.

- 16. For so far as Aristotle defines it as first driving force of the body, which has the power to live, he too wished to deceive readers and hearers.

Philosophy, especially Aristotle, helps us ask the right questions, but it is Christ, His incarnation, His death and resurrection, that gives us the answer, the truth of humanity. Man is created in God's image. And man is forgiven by Christ, justified man! Astonishing.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed