Thomas Aquinas wrote his little essay Being and Essence to teach priests a bit of Aristotle from a Christian perspective.

Here is the essay for you to read, with notes and charts added by Dr. Schulz:

Here is the essay for you to read, with notes and charts added by Dr. Schulz:

Here is the conversation with Dr Schulz and me about Aquinas' Phoenix:

| mastermetaphorsauqinasphoenix_mixdown.mp3 |

Here's are Dr. Schulz's suggestions for engaging this text;

Aquinas’ PhoenixThe Miller translation is found above for your reference, excerpted and with my own annotations and charts.

- Read Thomas Aquinas’ little book On Being and Essence (De Ente Et Essentia in Latin). Aquinas’ text is a must-read! An online reproducible and contemporary translation by Robert Miller is at http://www.theologywebsite.com/etext/aquinas/beingandessence.shtml. A more scholarly and footnoted translation online is the Fordham version at http://www.faculty.fordham.edu/klima/Blackwell-proofs/MP_C30.pdf

b) Let’s begin with the normative use of the term substance in the 4th-century AD Nicene Creed:

| Symbolum Nicaenum Credo in unum Deum, Patrem omnipotentem, factorem caeli et terrae,visibilium omnium et Et in unum Dominum Iesum Christum, Filium Dei unigenitum, et ex Patre natum ante omnia saecula. Deum de Deo, Lumen de Lumine, Deum verum de Deo vero, genitum non factum, consubstantialem Patri; per quem omnia facta sunt. | Nicene Creed I believe in one God, the Father almighty, maker of heaven and earth, and of all things visible and invisible. And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the only begotten Son of God, begotten of His Father before all worlds., God of God, Light of Light, very God of very God, begotten, not made, being of one substance with the Father, by whom all things were made |

There is a careful, detailed understanding of substance in traditional Western philosophy – a careful, detailed approach begun by Aristotle (384–322 BC) before Nicea and adapted by Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) the later Mediaeval period centuries after Nicea. The detailed philosophical work on substance is reflected in the so-called Tree of Porphyry, but painstakingly explained by Aquinas in his tutorial On Being and Essence.

- For starters, there is a brief but helpful introductory PowerPoint on Aquinas’ little book that’s viewable at www.ivc.edu/faculty/SFelder/Documents/Aquinas Being and Essence.ppt. You’ll find an exhaustive (and potentially exhausting!) analysis of Thomistic (or official Roman Catholic teaching) on Aquinas’ Being and Essence online at http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/05543b.htm.

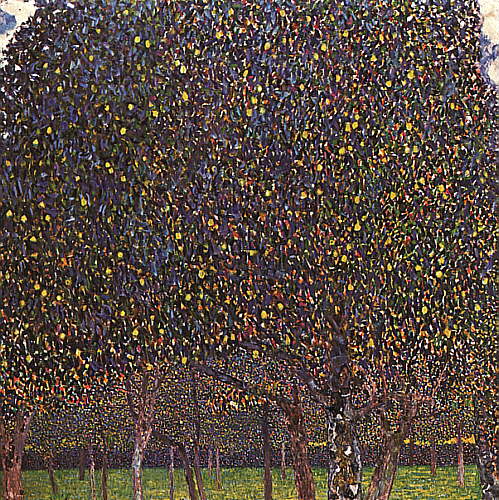

Diagram [of “essence ß à existence”] by Karl Jaspers

Q. How do we (professor, student, movie viewer or author) know that a phoenix is a phoenix?

- There are two key concepts to keep in heart and mind here, namely essence and existence. Aquinas’ analog for the concept of essence is something that everybody knows: What a phoenix is, even though there’s no such thing as a phoenix. Think of the Harry Potter story:

A. Via its essence.

Only one phoenix exists at a time. When the bird felt its death was near, every 500 to 1,461 years, it would build a nest of aromatic wood and set it on fire. The bird then was consumed by the flames. Then the phoenix would reappear sometime after its total disintegration.

e) Second key concept: Existence. Aquinas’ analog for the concept of existence is the human (type of) being.

Q. What’s the difference between the phoenix and the human being?

A. The human being (known as such essentially) also exists (it has being) – a decisive additional feature.

f) Crucial questions:

Q1. How do we “get” the essential concept of phoenix?

Q2. How is it that essences “stay put” so as to count as knowledge (see my dialogs Three Socratic Vignettes on Knowledge).

g) For the hearty appetite – and for perhaps a more pastorally usable consideration of substance and the question regarding the main lesson we learn from thinking and speaking about being or substance or essence, see Martin Heidegger’s What is Metaphysics? at http://www.wagner.wpengine.netdnacdn.com/psychology/files/2013/01/Heidegger.

There is a one-page summation of Heidegger’s rather different approach to the traditional Western philosophical understanding of essence at http://philosophypages.com/hy/7b.htm.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed