This hymn of Luther’s is not only used by Lutherans the world over. It is the Hymn of Protestantism. It would be hard to find a Protestant hymnal worthy of the name in which this hymn is not. It has been rightly called “the greatest hymn of the greatest man in the greatest period of German history.” Its wide appeal is best illustrated by the fact that no hymn has been translated into more languages than “Ein’ feste Burg.” (The Handbook to The Lutheran Hymnal, p. 193)

a very present help in trouble.

7 The Lord of hosts is with us;

the God of Jacob is our fortress. (ESV)

The following translation, now 100 years old, is from Common Service Book of the Lutheran Church (1917):

1 A mighty Fortress is our God,

A trusty Shield and Weapon;

He helps us free from every need

That hath us now o'ertaken.

The old bitter foe

Means us deadly woe;

Deep guile and great might

Are his dread arms in fight:

On earth is not his equal.

2 With might of ours can naught be done,

Soon were our loss effected;

But for us fights the Valiant One

Whom God Himself elected.

Ask ye, Who is this?

Jesus Christ it is,

Of Sabaoth Lord,

And there's none other God;

He holds the field for ever.

3 Though devils all the world should fill,

All watching to devour us,

We tremble not, we fear no ill,

They cannot overpower us.

This world's prince may still

Scowl fierce as he will;

He can harm us none;

He's judge, the deed is done,

One little word o'erthrows him.

4 The Word they still shall let remain,

Nor any thanks have for it;

He's by our side upon the plain

With His good gifts and Spirit,

Take they then our life,

Goods, fame, child, and wife,

When their worst is done,

They yet have nothing won:

The Kingdom ours remaineth.

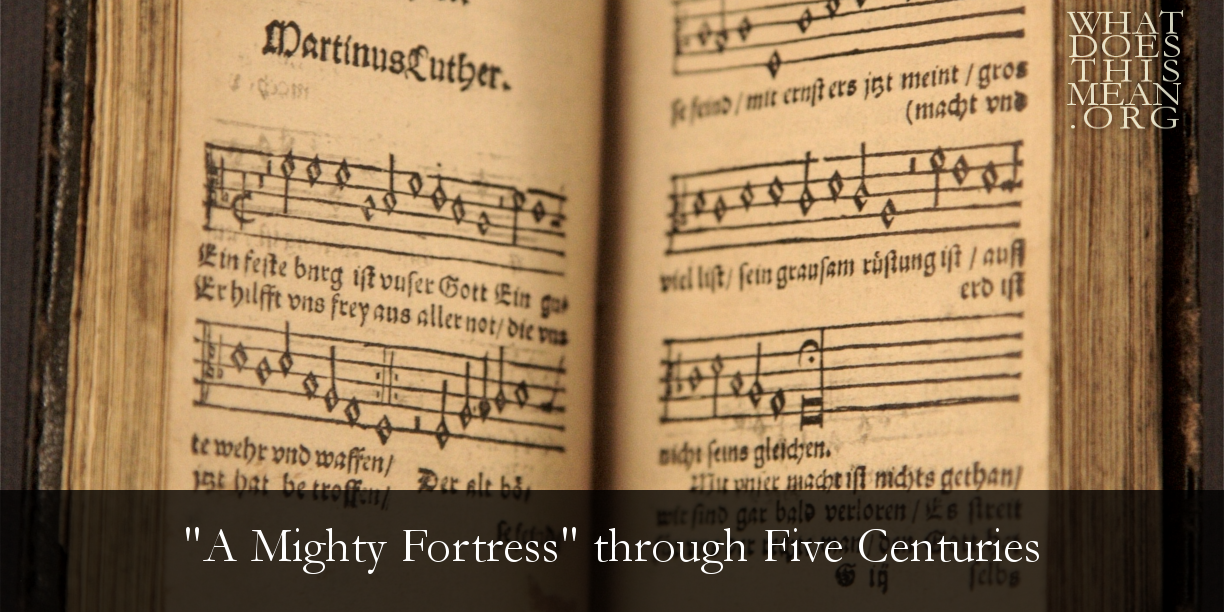

So what did Luther’s original text and tune look and sound like in his own time? The following video shows a “period score,” known as a broadsheet, which contains two stanzas of this hymn. Indeed, this hymn has been through so many evolutions, it behooves us during this 500th anniversary of the Reformation to go ad fontes (“to the source”) and recall what Luther had in mind when he penned this hymn in the late 1520’s. As you watch and listen to this video, ask yourself how this performance practice is different from hymn singing in our own day:

In the seventeenth century, Luther’s musical heirs made the most of this hymn, but in the musical language of their own day. In the days of Michael Praetorius (1571-1621), for instance, it was common to write chorale preludes, i.e., sacred works for organ that were based on familiar hymn tunes. The more elaborate version of the chorale prelude was the fantasia, as you will hear in the next video. I hesitate to invite the reader to watch an eleven-minute video, but I do not think you will be disappointed! Listen for the melody and its variations in the following video (the music starts at 0:52), which was filmed in Bach’s own St. Thomas Leipzig.

The Lutheran revival of the 19th century was somewhat unknowingly supported by the music of Mendelssohn. (He was a Reformed Christian with Lutheran association, but not a Lutheran confessor by any stretch of the imagination.) His revival of J. S. Bach’s St. Matthew Passion in 1829 was the first complete performance of this work outside of Bach’s Leipzig and since Bach’s death. We have documented in previous issues of “Lifted Voice” how Bach’s Mass in B Minor went behind the Iron Curtain in 1962, thereby going where the preacher cannot go—to the concert hall. So also the music of Mendelssohn and, to a lesser extent, Max Reger, whose elaborate music is more fitting for recitals than for church services. Even the youth and ethnicities featured in some of the videos in this column are a reminder that the message of the Reformation, like the Gospel itself, resounds around the world. From Luther’s occasional invitation to Philip Melanchthon (1497-1560) to sing a few stanzas of the 46th Psalm by themselves to the countless host that will sing this hymn with vigor on October 31, 2017, the message of justification by grace through faith will let all the world in every corner sing.

Come, fellow sons of the Reformation! Let us sing the 46th Psalm!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed