and it leads us to the hill of the crucified one.

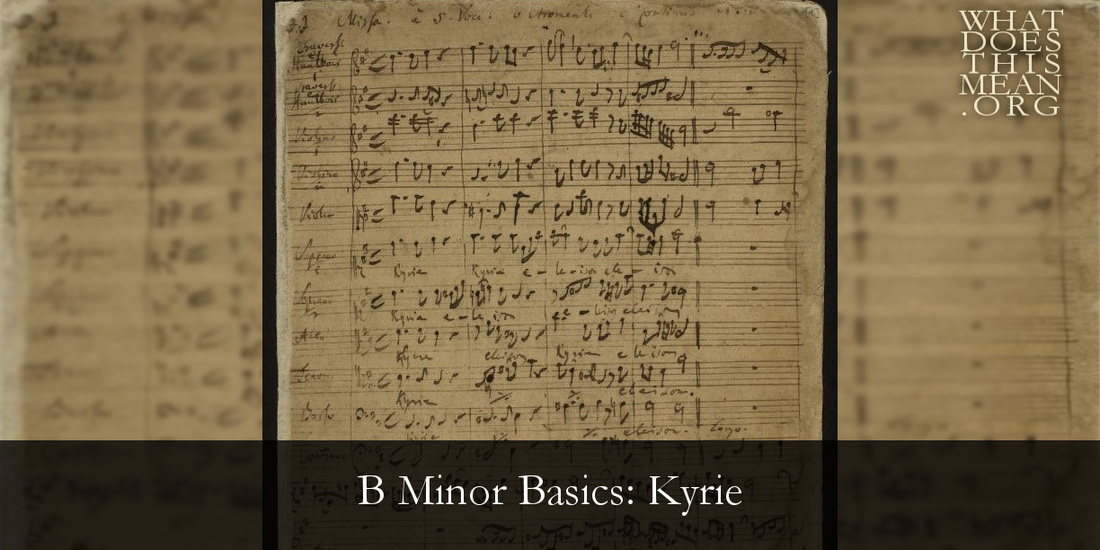

Kyrie I: Kyrie eleison + Lord, have mercy

In contrast to the full use of instruments, voices, and even musical forms, listen to the comparably transparent duet for treble voices and a handful of instruments on the words, “Christ, have mercy”. This is also one of few movement of the entire B Minor that is accessible to the parish that is blessed with a reasonably accomplished organist and one or more good treble voices for each vocal line:

Christe: Christe eleison + Christ, have mercy

- Kyrie! God, Father in heav’n above, You abound in gracious love, Of all things the maker and preserver. Eleison! Eleison!

- Kyrie! O Christ, our king, Salvation for all You came to bring. O Lord Jesus, God’s own Son, Our mediator at the heav’nly throne: Hear our cry and grant our supplication. Eleison! Eleison!

- Kyrie! O God the Holy Ghost, Guard our faith, the gift we need the most, And bless our life’s last hour, That we leave this sinful world with gladness. Eleison! Eleison!

(Lutheran Service Book [LSB] #942; emphasis added)

This Trinitarian text also demonstrates how the Kyrie is Christ-centered. See, for instance, how the second stanza of the hymn is the longest of the three and includes the greatest number of regal titles (Christ, king, God’s own Son, mediator) for the second person of the Trinity. So why did Bach chose to set the Christe movement, with its focus on God the Son, as a duet? The only other duet in the Kyrie-Gloria Mass was for the following words of the Gloria: “O Lord God, heavenly King, God the Father Almighty. O Lord, the only-begotten Son, Jesus Christ; O Lord God, Lamb of God, Son of the Father.” See how this text praises the Father and the Son. Similarly, the Christe addresses the Son as Christ, just after a prayer to the Father. Is it possible that Bach chose the duet, a two-voice form, to depict the mutual indwelling of Father and Son, and therefore the Divine and human natures of Christ? Set against the duet are the first and second violins in unison, which might depict the unity of the two natures, Divine and human, in the one person of Christ. Whatever Bach might have intended, the two-in-oneness is unmistakably present in the Christe.

The final Kyrie, sometimes called Kyrie II, returns to a minor key and to the full complement of voices and instruments in the traditional, imitative style of sixteenth-century church music:

Kyrie II: Kyrie eleison + Lord, have mercy

| O Lord, have mercy. O Christ, have mercy. O Lord, have mercy. O Christ, hear us. God the Father in heaven, have mercy. God the Son, Redeemer of the world, have mercy. God the Holy Spirit, have mercy. Be gracious to us. Spare us, good Lord. Be gracious to us. Help us, good Lord. From all sin, from all error, from all evil; From the crafts and assaults of the devil; from sudden and evil death … (LSB, p. 288) |

It has been just over fifty years since Robert Shaw was shocked to see an audience linger for 30 minutes after a performance of the B Minor Mass in Moscow, even though Soviet authorities usually censored such art as part of their misguided nationalism. The success of the B-Minor Mass behind the Iron Curtain should not surprise us, however, for it is the gospel set to music, and the gospel always thrives under pressure. In this regard, Bach’s setting of the Kyrie, a musical litany in its own right, could not be more timely for our own day. How do the righteous respond when the very foundation of our society has collapsed under the federalization of same-sex “marriage”? Rather than trust in princes, who are but mortal, the faithful watch and pray. And the Kyrie of Bach’s B-Minor Mass can lead the way in our Trinitarian, Christ-centered, and comprehensive plea for Divine clemency: “Lord, have mercy!”

Nota Bene: To hear the Kyrie in the context of the entire B Minor Mass, please enjoy the following performance on period instruments from BBC Proms:

RSS Feed

RSS Feed