Our business there will be the unending Alleluia.

The 84th psalm is a psalm of comfort. It praises God’s Word highly over all things and exhorts us to gladly give up all good things—glory, power, joy, and whatever we desire—that we may hold onto God’s Word. And if we should be like the doorkeeper, that is, the least of those in the temple, this would still be far better than to sit in the castles of the godless. For God’s Word (the psalmist says) gives victory, salvation, grace, glory, and all good things. Oh, how blessed are those who believe this and then keep it!

(Reading the Psalms with Luther, p. 200)

Jerusalem, thou city fair and high, Would God I were in thee!

My longing heart fain to thee would fly, It will not stay with me.

Far over vale and mountain, Far over field and plain,

It hastes to seek its fountain / And leave this world of pain.

(The Lutheran Hymnal [TLH] 619, st. 1)

The overall textual and philosophical emphasis is upon man’s acceptance of death which leads to triumph over death. In a letter to his friend [Karl] Reinthaler, Brahms admitted that he would have preferred calling the work A Human Requiem rather than A German Requiem--a Requiem for all mankind.

(Choral Masterworks from Bach to Britten, p. 77)

The psalm-setting explored in this column is central to this most comforting work, both in its context and in its content. Regarding context, is the fourth of what eventually became a seven-movement work for chorus, two soloists, and orchestra, making Psalm 84 (i.e., selected verses from Psalm 84) the central movement of the work. Regarding content, the concept of being blessed by God is an important theme to this most unique choral masterwork of consolation for the living. Being blessed by God in Christ, in this life and in the next, is especially prominent in the first, fourth, and seventh movements, thereby serving as the “book ends” and the centerpiece of A German Requiem. As you listen to what might as well be the sound track for heaven itself, notice how the music changes to paint the text throughout the movement, and yet, it is unified by multiple statements of “How lovely are your dwellings, Lord of Sabaoth!”

| 0:01 | Wie lieblich sind deine Wohnungen Herr Zebaoth! |

How lovely are your dwellings Lord of Sabaoth! |

| 1:18 | Meine Seele verlanget und segnet sich nach den Vorhöfen des Herrn; |

My soul longs and faints for the courts of the Lord. |

| 1:50 | Mein Leib und Seele freuen sich in dem lebendigen Gott. |

My body and soul rejoice In the living God. |

| 3:03 | Wohl denen, die in deinem Hause wohnen, |

Blessed are they that in your house, do dwell, |

| [Wie lieblich . . .] | [How Lovely . . .] | |

| 3:24 | die loben dich immerdar | they praise you evermore. |

| [Wie lieblich . . . ] | [How lovely . . . ] |

Brahms was notoriously self-critical, and his early opinion of this movement was no exception. He sent a copy to Clara Schumann (1819–1896) in the spring of 1865, along with a note that might evoke a smile from the modern reader: “[This movement] is probably the weakest part of the said German Requiem, but . . . it may have vanished into thin air before you come to Baden [for her next visit].” Well, what to say? Thank God for Clara’s most objective and insightful opinion of this movement, having only seen the score: “The chorus from the Requiem pleases me very much, it must sound beautiful.” And after actually hearing the entire Requiem in 1868, she said, “[It] has taken hold of me as no sacred music ever did before” (Michael Musgrave, Cambridge Music Handbooks: Brahms: A German Requiem, pp. 5, 9).

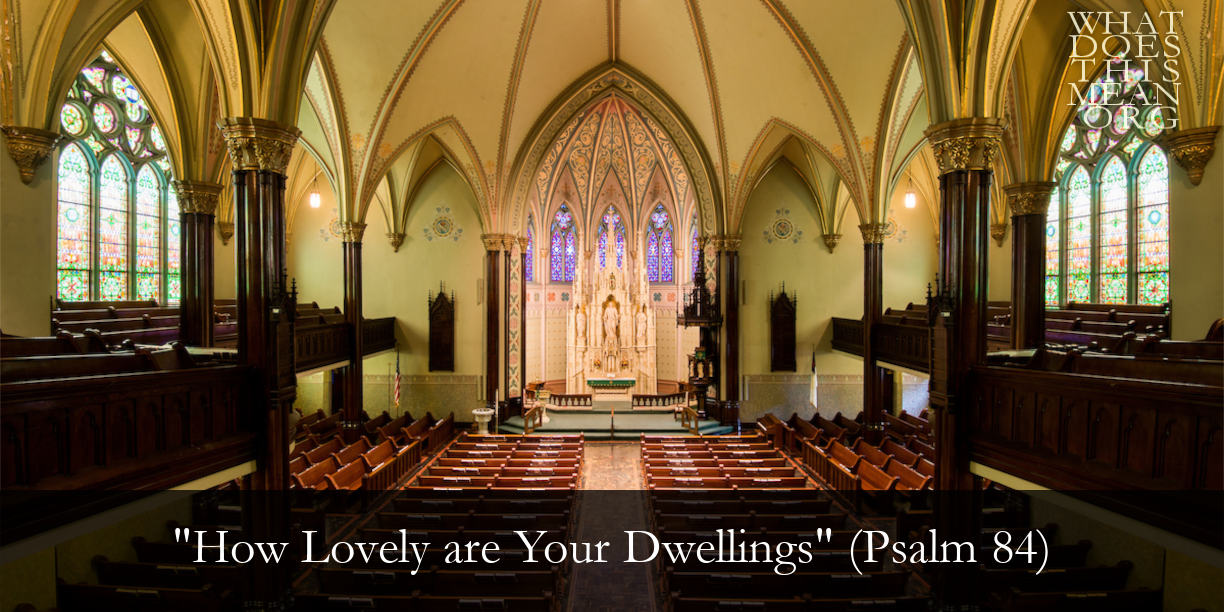

One faithful Lutheran layman in the Midwest echoed this sentiment when, after hearing this movement sung as a choral voluntary in the sanctuary pictured at the top of this column, he said to a friend sitting next to him, “Now that’s heaven!”

Unnumbered choirs before the shining throne / Their joyful anthems raise

Till heaven’s glad halls are echoing with the tones / Of that great hymn of praise

And all its host rejoices, And all its blessed throng

Unite their myriad voices / In one eternal song.

(TLH 619, st. 8)

+ + + + + + +

RSS Feed

RSS Feed