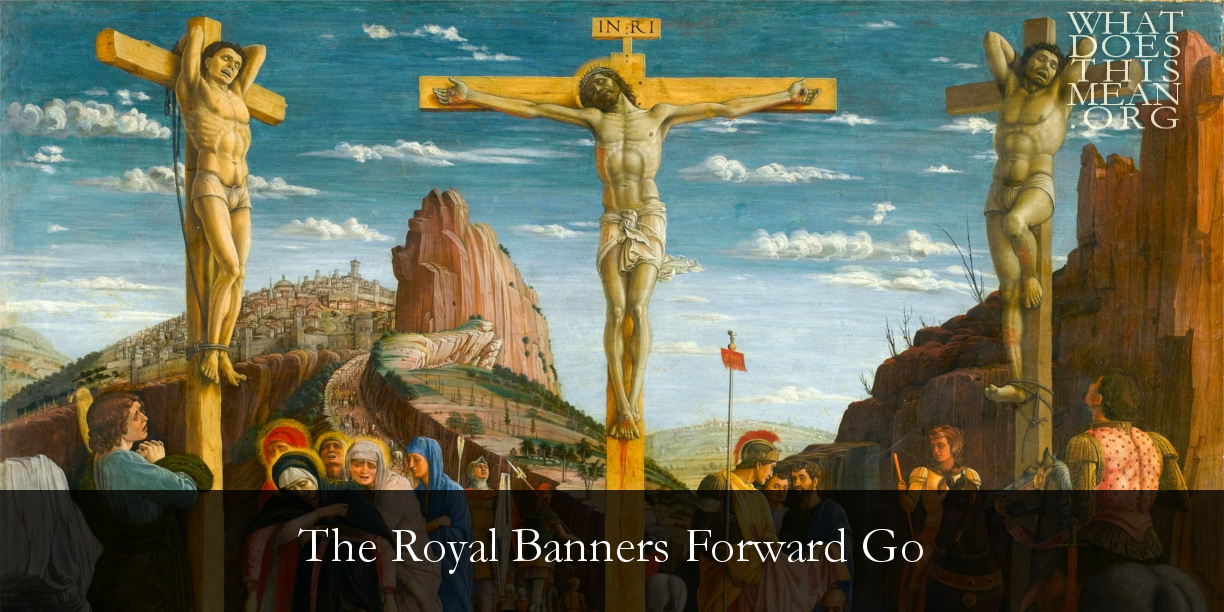

For behold, by the wood of Your cross joy has come into all the world!

| 1 The royal banners forward go; The cross shows forth redemption's flow, Where He, by whom our flesh was made, Our ransom in His flesh has paid: 2 Where deep for us the spear was dyed, Life's torrent rushing from His side, To wash us in the precious flood Where flowed the water and the blood. 3 Fulfilled is all that David told In sure prophetic song of old. That God the nations' king should be And reign in triumph from the tree. 4 O Tree of beauty, Tree of light, O Tree with royal purple dight;* Elect, on whose triumphal breast These holy limbs should find their rest. 5 On whose hard arms, so widely flung, The weight of this world's ransom hung, The price of humankind to pay And spoil the spoiler of his prey. 6 O Tree of beauty, tree most fair, Ordained those holy limbs to bear: Gone is thy shame, each crimsoned bough Proclaims the King of Glory now. 7 To Thee, eternal Three in One, Let homage meet by all be done, As by the cross Thou dost restore, So guide and keep us evermore. |

*The word “dight” in st. 4 means adorned, draped, or even equipped.

Though not listed in any of the sources that I consulted, a few texts on the precedent for banners/signals/ensigns come to mind. Moses’ instructions to the households in Numbers 2:2 during the wilderness wandering show the importance of banners in biblical times: “The people of Israel shall camp each by his own standard [signa], with the banners [vexilla] of their fathers’ houses.” The lifting up the bronze serpent in Numbers 21:8-9 describes the bronze serpent as a signo or sign to the people, setting the precedent for the lifting up of the Son of Man. To these one might also add St. Mark’s description of the cross, “And the inscription [titulus = banner] of the charge against him read, ‘The King of the Jews’” (15:26). The composite picture is certainly one of the Son of Man on the road to the cross, lifted up as the new and greater banner, sign, and serpent before the world.

The author, usually known simply as Fortunatus, was born in Italy and converted to Christianity at an early age. As the story goes, he almost lost his sight while he was a young student of poetry, but his sight was restored when he was anointed with oil sent by a friend, Gregory of Tours, which the latter had taken from a lamp that burned before the altar of St. Martin of Tours. This story led Fortunatus to make a pilgrimage to the shrine of St. Martin of Tours. He subsequently spent the rest of his life in Gaul, where he wrote Life of St. Martin of Tours and the now lost collection, Hymns for all the Festivals of the Church Year.

Two aspects of this brief biography impacted the sacred text at hand. First, the author’s knowledge of St. Martin of Tours, Patron Saint of the Military, made the author a good candidate to write a hymn that describes the cross as a military standard or ensign. Second, the province of Gaul was one of two epicenters for the development of plain chant, along with Rome. Considering this background, it is no surprise that “The Royal Banners” is a wonderful marriage of text and tune, as is the case with the new tunes that have been paired for his other surviving hymns, “Sing, My Tongue, the Glorious Battle” and “Hail Thee, Festival Day.”

Listen now to stanzas 1, 3, 4, and 7, as performed by The Cathedral Singers under the capable direction of Richard Proulx. The organ introduction slowly introduces the plain chant. Stanzas 1, 3, and 4 (please see the text above) are sung by women’s voices. The seventh stanza is sung in parallel octaves, with the addition of hand bells. Note that this sung text is slightly different from the translation above.

With the plain chant fresh in your tonal memory, now listen to the following setting by the Spanish priest, composer, and performer, Tomás Luis de Victoria (c. 1548 – 1611), who alternates between a slightly modified plain chant setting for unison voices (stz. 1, 3, and 5) and a motet setting for multiple voices (stz. 2, 4, 6, and 7). As you listen to the motet stanzas, try to hear how each voice imitates the previous voice, as each vocal part seems to weave its way to heaven:

Of course, you might be thinking that these musical settings are a bit daunting for the musical resources in your parish. “The Royal Banners” is also available as a hymn, with a congregational melody that is adapted from the plain chant:

Congregations who wish to express the fullness of “The Royal Banners” might make use of the practice of alternation, with the trained singers singing the chant stanzas (maybe odd-numbered stanzas?) and the congregation singing the simpler version for the remaining stanzas.

The context for “The Royal Banners” is of course Passiontide. In the three-year lectionary, it is fitting for Palm Sunday, for any day of Holy Week, and especially for Good Friday. LSB Altar Book lists “The Royal Banners” as the suggested hymn to depart after the Chief Service for Good Friday (p. 524). In my estimation, this placement is difficult to surpass because it equips the faithful to leave the sanctuary in the quiet confidence that “Fulfilled is all that David told,” etc. In the one-year lectionary, Lent V is Passion Sunday, which is where The Brotherhood Prayerbook places this hymn, as a companion to the high priestly Christology of Hebrews 9:11-15. It is also fitting for Holy Cross Day (September 14), especially for the theology of the cross in the Epistle Lesson, I Corinthians 1:18-25, which “drives the verbs” in “The Royal Banners Forward Go.”

The website, www.hymnary.org, cites a certain Greg Scheer on the Christ-centered nature of “The Royal Banners”: “Nowhere is the work of the cross so poignantly portrayed as in these immortal lines” (https://hymnary.org/text/the_royal_banners_forward_go; accessed 3/19/18). The author might overstate the situation, especially in light of the rich repository of hymns for Holy Week that the Lord has gifted to His church. I believe the author is correct, however, in noting the cross-centered nature of the hymn, as long as one understands the hymn as a sung sermon on the theology of the cross, not as adoration of the actual cross of wood. In this text, the crucified One is hard at work for you and for your salvation. As the historic liturgical text for Good Friday puts it:

| We adore You, O Lord, and we praise and glorify Your holy resurrection. For behold, by the wood of Your cross joy has come into all the world. God be merciful to us and bless us, and cause His face to shine upon us, and have mercy upon us. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed