I would my true love did so chance

To see the legend of my play,

To call my true love to my dance;

Chorus

Sing, oh! my love, oh! my love, my love, my love,

This have I done for my true love.

Then was I born of a virgin pure,

Of her I took fleshly substance

Thus was I knit to man's nature

To call my true love to my dance.

Chorus

In a manger laid, and wrapped I was

So very poor, this was my chance

Between an ox and a silly poor ass

To call my true love to my dance.

Chorus

Then afterwards baptized I was;

The Holy Ghost on me did glance,

My Father’s voice heard I from above,

To call my true love to my dance.

Chorus

Scholars generally agree that this anonymous text is rooted in Medieval piety. The text likely originated as part of the Medieval drama, which developed in three principle forms: the miracle play, the mystery play, and the morality play. Miracle plays were normally based on miracles associated with each saint. The mystery play, which is the most likely “home stage” of this text, was based on scriptural episodes, such as the resurrection, the creation, and the day of final judgment. Morality plays had a moral or allegorical tale as their basis, although they probably post-date the text at hand. If indeed “Dancing Day” originated as part of a mystery play, then it might have been sung to proclaim the miracle that Christ has takes His churchly bride (Jn. 3:29; 2 Cor. 11:2; Eph. 5:23; Rev. 19:7; 21:9) to Himself. If that is the case, then the phrase, “the legend of my play” pictures the drama of Christ saving and seeking His church. In the wake of His death and resurrection (“tomorrow”), He “dances” with His churchly bride (His “true love” [Is. 62:4-5; Jer. 2:2; Hos. 2:21-22]) at the royal wedding feast.

The reader who is not familiar with “Dancing Day” might be struck by the Vox Christi or “Voice of Christ” method, in which Christ speak to His bride, the church, and declares all that He has done for her as His one true love. This is a relatively rare device in our hymnody, although most readers of “Lifted Voice” might be familiar with J. S. Bach’s use of dialogues between Christ and His church in many of his sacred cantatas, as well as Luther’s use of the technique in his hymn, “Dear Christians, One and All, Rejoice”:

| He spoke to His beloved Son: ‘Tis time to have compassion. Then go bright Jewel of my crown, And bring to men salvation; From sin and sorrow set him free, Slay bitter death for him that he May live with Thee forever. |

| To me He spake: Hold fast to Me, I am thy Rock and Castle; Thy ransom I Myself will be, For thee I strive and wrestle; For I am with thee, I am thine, And evermore thou shalt be Mine: The Foe shall not divide us. — TLH 387.7 |

For thirty pence Judas me sold,

His covetousness for to advance:

Mark whom I kiss, the same do hold!

The same is he shall lead the dance.

Chorus

Before Pilate the Jews me brought,

Where Barabbas had deliverance;

They scourged me and set me at nought,

Judged me to die to lead the dance.

Chorus

Then on the cross hanged I was,

Where a spear my heart did glance;

There issued forth both water and blood,

To call my true love to my dance.

Chorus

To my best knowledge, these three stanzas have not been set to music, which explains why “Dancing Day” is usually sung for Christmas or Epiphany. And the references to “the Jews,” which simply narrate Jesus’ persecution by the unbelieving Jews, would not survive today’s postmodern mind! The stanzas on Christ’s Passion, however, are worth incorporating into the church bulletin or even into the sermon for the sake of the “for us” principle of Christian theology. For us Christ was kissed by Judas so He could lead us in the dance of salvation. For us He traded places with Barabbas so we could be set free from the death sentence that we inherited since Adam. For us Christ was hanged on the cross and pierced with a spear, so that water and blood from His side would create a churchly Bride for Himself (I Jn. 5:8) and call her to the sacramental wedding feast.

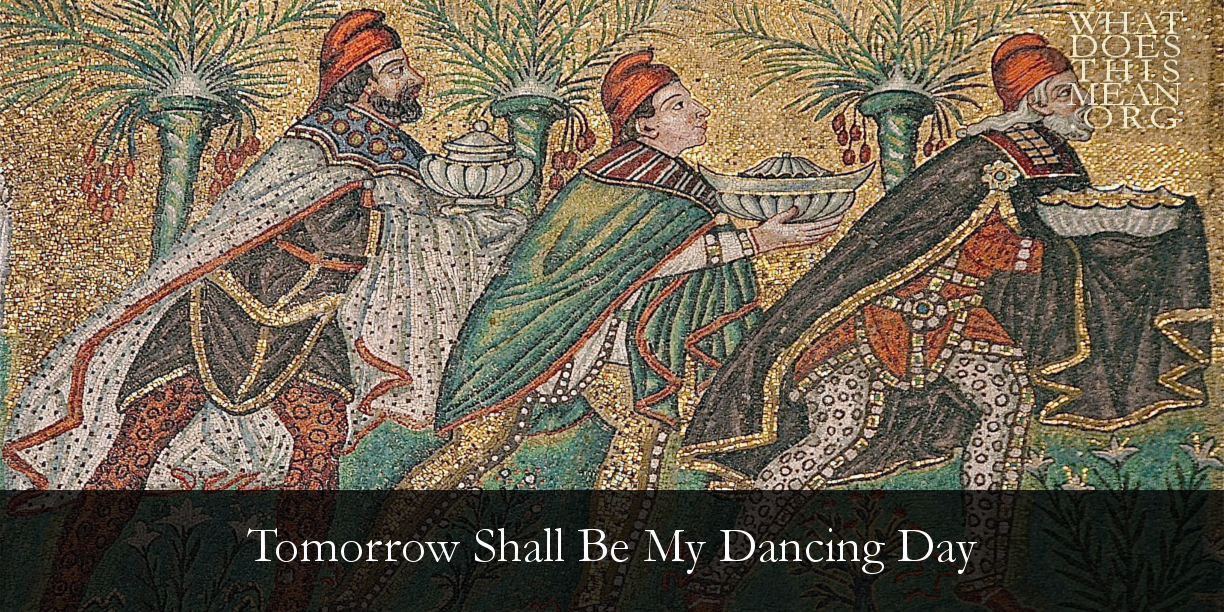

It is no surprise, then, that the rich imagery of the person and work of Christ in “Dancing Day” has inspired several composers to set the first four stanzas to music. (The three I have chosen for this column, by the way, are all twentieth century British composers, who probably have a deeper understanding of royalty and feasting than many Americans.) In the following setting by England’s late Sir David Willcocks (1919-2015), listen to the lively ¾ meter, which is closely associated with Medieval dance. Notice how the text “rides the wave” of the music and is fitting for the joyful union of Christ and His church:

In his masterful study, Martin Luther’s Doctrine of Christ, Ian D. Kingston Siggins describes Luther’s understanding of the union between Christ and His church: “The bride cannot rest or be satisfied until she has only her beloved; and Christ, too, will have His bride only, and none beside” (p. 260). This is precisely the point of “Dancing Day” and the liturgical cycle from Christmas Day through Epiphany: Christ has done all for you, His bride, that you might have what the Collect for Epiphany Day calls “the fruition of [His] glorious Godhead” (TLH p. 58). That is to say, the One who took fleshly substance and was knit to your nature in order to share with you all the fruits of His Godhead: life, salvation, and resurrection from the dead.

This He has done for you, His true love!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed