of that science which I have achieved in musique, with the submissive prayer

that Your Highness will look upon it with most gracious eyes …

the Kyrie-Gloria Mass, 1733

The Qui tollis (please see the complete text and translation below) presents a unique opportunity to the composer since it contains the first reference in the Kyrie-Gloria to Jesus’ Passion: “Thou that takest away the sin of the world,” etc. Bach reduces the voicing from five parts (SSATB) to four (SATB), with the top part specifically marked “Soprano II”—a feature that he uses only one other time in the complete B Minor, viz. for the Crucifixus. The tempo is marked “Lento,” which might be a less-than-subtle hint that the text of the Gloria is now shifting, if only briefly, to the theology of the cross and the self-offering of the Lamb of God, which is a special focus of the Lenten season. Two flutes hover above the orchestra and voices, a soothing and yet somehow disturbing presence. The lower strings pulsate in quarter notes, while the violas “slice through the texture with sighs of lamentation” (John Eliot Gardiner, Bach: Music in the Castle of Heaven, p. 495). The mood is tranquil, even heavy at times, for the most serious moment in the Gloria:

| Qui tollis peccata mundi, misere nobis. Qui tollis peccata mundi, Suscipe deprecationem nostram. | Thou that takest away the sin of the world, have mercy upon us. Thou that takest away the sin of the world, receive our prayer. |

| Qui sedes ad Dextram Patris, miserere nobis. | Thou that sittest at the right hand of the Father, have mercy upon us. |

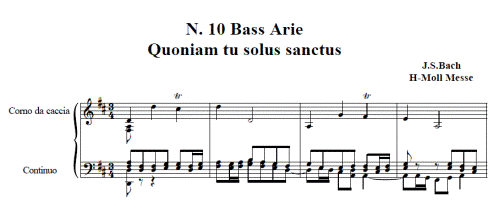

| The final aria in the Gloria, the Quoniam, is perhaps the most unique of the movements featured in this article, if not in the entire Kyrie-Gloria Mass. The scoring alone is unique, if not bizarre: the rarely-used Corno da caccia or “hunting horn,” two bassoons, and basso continuo (harpsichord and cello). The net effect, with the hunting horn in the upper register and the bassoons in the lower register, is indeed that of “the highest,” a perfect fit for the words, “the most high, Jesus Christ.” |

| Quoniam tu solus Sanctus, Tu solus Dominus, Tu solus Altissimus, Jesu Christe. | For Thou only art holy; Thou only art the Lord. Thou only art the most high, Jesus Christ. |

| Cum Sancto Spiritu in Gloria Dei Patris Amen. | With the Holy Spirit In the glory of God the Father. Amen. |

And yet, even though the history of the performance of the Kyrie and Gloria in Bach’s day is sketchy, and even if Bach truly thought of the Kyrie-Gloria Mass as a “trifle of a work” (my translation), it is safe to say, nearly 300 years later, that George Stauffer was quite correct in saying, “The Kyrie and Gloria represent the apotheosis of Bach’s Leipzig cantata style” (Bach: The Mass in B Minor: The Great Catholic Mass, p. 97). In other words, these two movements might be the apex of his sacred music composed for worship during his tenure in Leipzig (1723-1750). Indeed, is it possible that Bach could have left the Kyrie-Gloria in tact, with no further additions, and it would still be looked upon “with most gracious eyes” as one of the greatest choral-orchestral masterworks for the ages?

Electors, employers, and my humble analysis aside, the words appended to the end of the Gloria in the autograph of the Kyrie-Gloria Mass summarize the theology of this Mass and of all sacred music that gives us voice to sing the Gospel: “Fine. SDG.” That is to say, “It is finished. Soli Deo Gloria (Glory to God alone).”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed